Home › Forum Online Discussion › General › Why some Japanese pensioners want to go to jail (article)

- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 6 years, 10 months ago by

c_howdy.

-

AuthorPosts

-

April 23, 2019 at 12:11 pm #58608

c_howdy

Participant

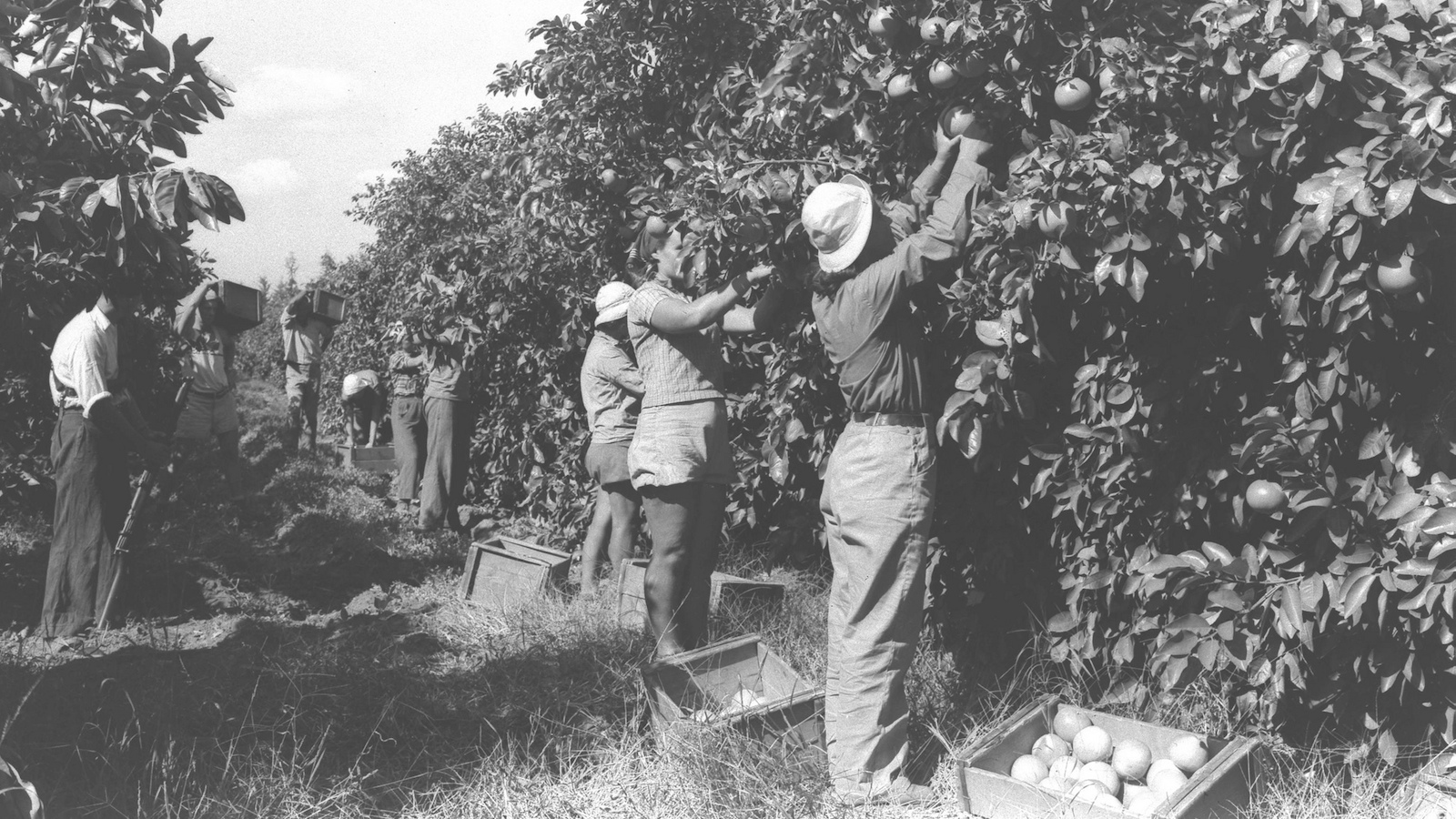

A kibbutz (Hebrew: קִבּוּץ / קיבוץ, lit. “gathering, clustering”; regular plural kibbutzim קִבּוּצִים / קיבוצים) is a collective community in Israel that was traditionally based on agriculture. The first kibbutz, established in 1909, was Degania. Today, farming has been partly supplanted by other economic branches, including industrial plants and high-tech enterprises. Kibbutzim began as utopian communities, a combination of socialism and Zionism. In recent decades, some kibbutzim have been privatized and changes have been made in the communal lifestyle. A member of a kibbutz is called a kibbutznik (Hebrew: קִבּוּצְנִיק / קיבוצניק; plural kibbutznikim or kibbutzniks).

-https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kibbutz-

https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-47033704

31 January 2019

Japan is in the grip of an elderly crime wave – the proportion of crimes committed by people over the age of 65 has been steadily increasing for 20 years. The BBC’s Ed Butler asks why.

At a halfway house in Hiroshima – for criminals who are being released from jail back into the community – 69-year-old Toshio Takata tells me he broke the law because he was poor. He wanted somewhere to live free of charge, even if it was behind bars.

“I reached pension age and then I ran out of money. So it occurred to me – perhaps I could live for free if I lived in jail,” he says.

“So I took a bicycle and rode it to the police station and told the guy there: ‘Look, I took this.'”

The plan worked. This was Toshio’s first offence, committed when he was 62, but Japanese courts treat petty theft seriously, so it was enough to get him a one-year sentence.

Small, slender, and with a tendency to giggle, Toshio looks nothing like a habitual criminal, much less someone who’d threaten women with knives. But after he was released from his first sentence, that’s exactly what he did.

“I went to a park and just threatened them. I wasn’t intending to do any harm. I just showed the knife to them hoping one of them would call the police. One did.”

Altogether, Toshio has spent half of the last eight years in jail.

I ask him if he likes being in prison, and he points out an additional financial upside – his pension continues to be paid even while he’s inside.

“It’s not that I like it but I can stay there for free,” he says. “And when I get out I have saved some money. So it is not that painful.”

Toshio represents a striking trend in Japanese crime. In a remarkably law-abiding society, a rapidly growing proportion of crimes is carried about by over-65s. In 1997 this age group accounted for about one in 20 convictions but 20 years later the figure had grown to more than one in five – a rate that far outstrips the growth of the over-65s as a proportion of the population (though they now make up more than a quarter of the total).

And like Toshio, many of these elderly lawbreakers are repeat offenders. Of the 2,500 over-65s convicted in 2016, more than a third had more than five previous convictions.

Another example is Keiko (not her real name). Seventy years old, small, and neatly presented, she also tells me that it was poverty that was her undoing.

“I couldn’t get along with my husband. I had nowhere to live and no place to stay. So it became my only choice: to steal,” she says. “Even women in their 80s who can’t properly walk are committing crime. It’s because they can’t find food, money.”

We spoke some months ago in an ex-offender’s hostel. I’ve been told she’s since been re-arrested, and is now serving another jail-term for shoplifting.

Japan’s Elderly Crime Wave can be heard on Assignment on the BBC World Service from Thursday 31 January – click here for transmission times

Or listen now online

Theft, principally shoplifting, is overwhelmingly the biggest crime committed by elderly offenders. They mostly steal food worth less than 3,000 yen (£20) from a shop they visit regularly.Michael Newman, an Australian-born demographer with the Tokyo-based research house, Custom Products Research Group points out that the “measly” basic state pension in Japan is very hard to live on.

In a paper published in 2016 he calculates that the costs of rent, food and healthcare alone will leave recipients in debt if they have no other income – and that’s before they’ve paid for heating or clothes. In the past it was traditional for children to look after their parents, but in the provinces a lack of economic opportunities has led many younger people to move away, leaving their parents to fend for themselves.

“The pensioners don’t want to be a burden to their children, and feel that if they can’t survive on the state pension then pretty much the only way not to be a burden is to shuffle themselves away into prison,” he says.

The repeat offending is a way “to get back into prison” where there are three square meals a day and no bills, he says.

“It’s almost as though you’re rolled out, so you roll yourself back in.”

Newman points out that suicide is also becoming more common among the elderly – another way for them to fulfil what he they may regard as “their duty to bow out”.

The director of “With Hiroshima”, the rehabilitation centre where I met Toshio Takata, also thinks changes in Japanese families have contributed to the elderly crime wave, but he emphasises the psychological consequences not the financial ones.

“Ultimately the relationship among people has changed. People have become more isolated. They don’t find a place to be in this society. They cannot put up with their loneliness,” says Kanichi Yamada, an 85-year-old who as a child was pulled out of the rubble of his home when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

“Among the elderly who commit crimes a number have this turning point in their middle life. There is some trigger. They lose a wife or children and they just can’t cope with that… Usually people don’t commit crime if they have people to look after them and provide them with support.”

Toshio’s story about being driven to crime as a result of poverty is just an “excuse”, Kanichi Yamada suggests. The core of the problem is his loneliness. And one factor that may have prompted him to reoffend, he speculates, was the promise of company in jail.

It’s true that Toshio is alone in the world. His parents are dead, and he has lost contact with two older brothers, who don’t answer his calls. He has also lost contact with his two ex-wives, both of whom he divorced, and his three children.

I ask him if he thinks things would have turned out differently if he’d had a wife and family. He says they would.

“If they had been around to support me I wouldn’t have done this,” he says.

Michael Newman has watched as the Japanese government has expanded prison capacity, and recruited additional female prison guards (the number of elderly women criminals is rising particularly fast, though from a low base). He’s also noted the steeply rising bill for medical treatment of people in prison.

There have been other changes too, as I see for myself at a prison in Fuchu, outside Tokyo, where nearly a third of the inmates are now over 60.

There’s a lot of marching inside Japanese prisons – marching and shouting. But here the military drill seems to be getting harder to enforce. I see a couple of grey-haired inmates at the back of one platoon struggling to keep up. One is on crutches.

“We have had to improve the facilities here,” Masatsugu Yazawa, the prison’s head of education tells me. “We’ve put in handrails, special toilets. There are classes for older offenders.”

He takes me to watch one of them. It begins with a karaoke rendition of a popular song, The Reason I was Born, all about the meaning of life. The inmates are encouraged to sing along. Some look quite moved.

“We sing to show them that the real life is outside prison, and that happiness is there,” Yazawa says. “But still they think the life in prison is better and many come back.”

Michael Newman argues that it would be far better – and much cheaper – to look after the elderly without the expense of court proceedings and incarceration.

“We actually costed a model to build an industrial complex retirement village where people would forfeit half their pension but get free food, free board and healthcare and so on, and get to play karaoke or gate-ball with the other residents and have a relative amount of freedom. It would cost way less than what the government’s spending at the moment,” he says.

But he also suggests that the tendency for Japanese courts to hand down custodial sentences for petty theft “is slightly bizarre, in terms of the punishment actually fitting the crime”.

“The theft of a 200-yen (£1.40) sandwich could lead to an 8.4m-yen (£58,000) tax bill to provide for a two-year sentence,” he writes in his 2016 report.

That may be a hypothetical example, but I met one elderly jailbird whose experience was almost identical. He’d been given a two-year jail term for only his second offence: stealing a bottle of peppers worth £2.50.

And I heard from Morio Mochizuki, who provides security for some 3,000 retail outlets in Japan, that if anything the courts are getting tougher on shoplifters.

“Even if they only stole one piece of bread,” says Masayuki Sho of Japan’s Prison Service, “it was decided at trial that it is appropriate for them to go to prison, therefore we need to teach them the way: how to live in society without committing crime.”

I don’t know whether the prison service has taught Toshio Takata this lesson, but when I ask him if he is already planning his next crime, he denies it.

“No, actually this is it,” he says.

“I don’t want to do this again, and I will soon be 70 and I will be old and frail the next time. I won’t do that again.”

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.